North Carolina’s opioid crisis has led to aggressive prosecution of drug-related deaths through “death by distribution” charges. If you’re facing these serious allegations or worried about potential charges, understanding the law is crucial. This article explains North Carolina’s death by distribution statute, what prosecutors must prove, and why immediate legal representation matters.

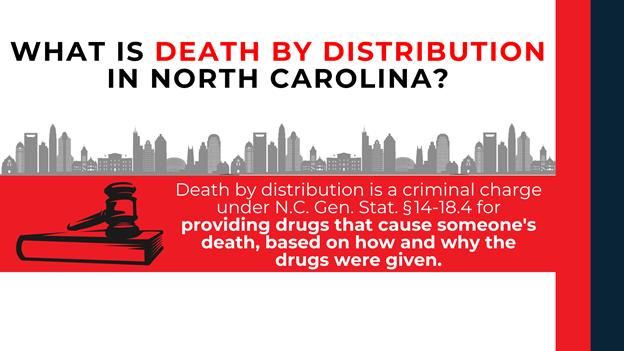

What Is Death by Distribution in North Carolina?

Death by distribution refers to criminal charges filed when someone dies after using drugs provided by another person. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-18.4, the law creates several distinct offenses based on how the drugs were provided and the defendant’s state of mind.

The North Carolina General Assembly first enacted this law in 2019 to address the devastating impact of the opioid epidemic. In 2023, lawmakers significantly expanded the statute, making it easier for prosecutors to file charges and increasing potential penalties.

The law recognizes four main categories of death by distribution:

- Distribution without sale (Class C felony)

- Distribution with malice (Class B2 felony)

- Sale resulting in death (Class B2 felony)

- Aggravated sale (Class B1 felony)

Each category has specific elements prosecutors must prove beyond a reasonable doubt.

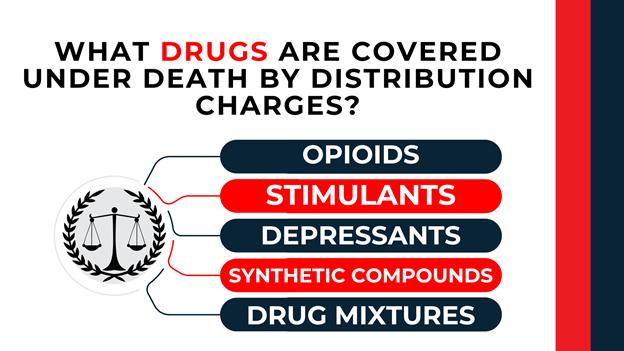

What Drugs Are Covered Under Death by Distribution Charges?

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-18.4(d) defines “certain controlled substances” covered by the law. These include:

- Opioids: Any opium, opiate, or opioid, including heroin, fentanyl, and prescription painkillers

- Stimulants: Cocaine and methamphetamine

- Depressants: Substances classified as depressants under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 90-92(a)(1)

- Synthetic compounds: Any synthetic or natural salt, compound, derivative, or preparation of the above substances

- Drug mixtures: Any combination containing these controlled substances

The statute specifically excludes decocainized coca leaves and extractions that don’t contain cocaine or ecgonine. This broad definition means prosecutors can pursue charges for deaths involving street drugs, prescription medications, or any mixture containing these substances.

How Does the Prosecution Prove Death by Distribution?

To secure a conviction, prosecutors must establish specific elements depending on which subsection they charge under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-18.4.

For Basic Distribution Charges (Without Sale)

Under subsection (a1), the state must prove:

- The defendant unlawfully delivered at least one controlled substance

- The victim’s ingestion of that substance caused their death

- The defendant’s delivery was the proximate cause of death

“Unlawful delivery” means providing drugs without legal authorization. This could include sharing drugs at a party, giving pills to a friend, or any transfer without a valid prescription or license.

For Distribution with Malice

Subsection (a2) requires all the above elements plus proof that “the person acted with malice.” Malice in this context follows criminal law principles—it may include intent to harm or reckless disregard for human life.

For Sale-Based Charges

Under subsection (b), prosecutors must show:

- The defendant unlawfully sold controlled substances

- The buyer’s ingestion caused their death

- The sale was the proximate cause of death

A “sale” requires an exchange for something of value, distinguishing it from mere sharing or distribution.

For Aggravated Sale Charges

Subsection (c) includes all elements of a sale plus a qualifying prior conviction within 10 years. Qualifying convictions include:

- Previous death by distribution convictions

- Drug manufacturing or trafficking under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 90-95

- Similar federal or out-of-state drug convictions

What Are the Legal Elements of Proximate Cause?

Proximate cause represents one of the most complex elements in death by distribution cases. The prosecution must prove the defendant’s actions were a direct and foreseeable cause of death—not merely that drugs were involved.

Courts examine several factors:

- Foreseeability: Was death a reasonably foreseeable consequence of providing these drugs?

- Intervening causes: Did other factors break the causal chain between delivery and death?

- Time gap: How much time elapsed between delivery and death?

- Victim’s actions: Did the victim’s own conduct contribute to the fatal outcome?

If the victim obtained drugs from multiple sources, mixed substances, or took amounts far exceeding what the defendant provided, establishing proximate cause becomes more difficult for prosecutors.

What Defenses Apply to Death by Distribution Charges?

Several defenses may apply depending on the facts of your case. Rather than existing separately, these defenses often challenge specific elements the prosecution must prove.

Challenging Unlawful Delivery or Sale

If the defendant had legal authority to provide the substance, no crime occurred. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-18.4(g) specifically exempts:

- Valid prescriptions issued by licensed practitioners

- Pharmacy dispensing pursuant to prescriptions

- Legal administration by healthcare providers

Disputing Causation

The defense may argue the defendant’s actions didn’t proximately cause death. This could involve showing:

- The victim obtained drugs from other sources

- Medical evidence points to different causes of death

- Too much time passed between delivery and death

- The victim’s own reckless behavior was the primary cause

Lack of Knowledge

While not explicitly stated in the statute, general criminal law principles may allow defendants to argue they didn’t know they were delivering controlled substances or couldn’t foresee the risk of death.

Good Samaritan Protections

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-18.4(f) preserves rights under the Good Samaritan law. If someone calls 911 seeking help for an overdose, they may have immunity from certain drug charges—though this protection has limits discussed below.

Can Good Samaritan Laws Protect Against Death by Distribution Charges?

North Carolina’s Good Samaritan statute, N.C. Gen. Stat. § 90-96.2, provides limited immunity for people who seek medical help during overdoses. However, the death by distribution statute explicitly states it doesn’t restrict these protections.

To qualify for Good Samaritan immunity, someone must:

- Call 911, law enforcement, or EMS for an overdose victim

- Act in good faith believing they’re the first to call

- Provide their real name to responders

- Not be executing an arrest warrant or search

The 2023 amendments expanded protections to include possession of less than one gram of any controlled substance, not just opioids and cocaine.

Important limitation: Good Samaritan laws protect against possession charges, not distribution or sale charges. If someone sold drugs that caused an overdose, calling 911 won’t provide immunity from death by distribution prosecution.

What’s the Difference Between Death by Distribution and Murder Charges?

Death by distribution occupies a unique space between drug crimes and homicide. Understanding the distinctions helps grasp the severity of these charges.

Second-Degree Murder

Before 2019, prosecutors sometimes charged drug dealers with second-degree murder under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-17(b) when buyers died from overdoses. The 2023 amendments eliminated the provision reducing drug-related murder to a Class B2 felony, meaning such cases now face standard murder penalties.

Key Differences

- Intent: Murder requires malice; basic death by distribution doesn’t

- Penalties: Murder charges typically carry more severe consequences

- Elements: Death by distribution has specific statutory requirements; murder relies on common law principles

- Defenses: Different defenses may apply to each charge

Prosecutors may charge both offenses, letting juries decide which fits the evidence.

How Have Recent Changes Affected Death by Distribution Laws?

The 2023 amendments to N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-18.4 made several significant changes:

Expanded Scope

The new law created distribution-only offenses not requiring a sale. This means prosecutors can now charge people who share drugs without exchanging money or value—dramatically expanding potential defendants.

Increased Penalties

- Basic sale offenses increased from Class C to Class B2 felonies

- Aggravated offenses rose from Class B2 to Class B1 felonies

- The lookback period for prior convictions extended from 7 to 10 years

Removed Barriers

The original law required proving defendants acted “without malice” for basic charges. Removing this requirement simplified prosecution—now the presence or absence of malice only affects which subsection applies.

Enhanced Protections

Good Samaritan immunity expanded to cover possession of any controlled substance under one gram, not just opioids and cocaine.

Should I Contact a Lawyer for Death by Distribution Charges?

Death by distribution charges carry severe felony penalties that can result in substantial prison time. The complexity of these cases—involving medical evidence, causation issues, and evolving law—makes experienced legal representation essential.

Acting quickly matters because:

- Evidence disappears or degrades over time

- Witness memories fade

- Early intervention may prevent charges or reduce their severity

- Constitutional rights need protection from the start

The consequences of a conviction extend beyond criminal penalties. A felony record affects employment, housing, professional licenses, and countless other aspects of life.

Take Action to Protect Your Rights

If you’re facing death by distribution charges or concerned about potential prosecution, don’t wait to seek legal help. The stakes are too high to navigate this complex area of law alone.

Patrick Roberts Law has extensive experience defending clients against serious criminal charges throughout North Carolina.* Attorney Patrick Roberts understands the nuances of drug crime defense and works tirelessly to protect clients’ rights and futures.

Contact Patrick Roberts Law today for a consultation about your case. Early intervention by knowledgeable counsel can make a significant difference in the outcome of death by distribution charges. Call now to discuss your situation and learn about your legal options.

*Disclaimer: Each case is different and must be evaluated separately. Prior results achieved do not guarantee similar results can be achieved in future cases.