When a family member calls from jail or a loved one faces criminal charges, the immediate concern becomes getting them released. In that stressful moment, terms like “bail” and “bond” get thrown around, often interchangeably, adding confusion to an already overwhelming situation. Understanding what these terms actually mean under North Carolina law helps families make informed decisions about pretrial release and the financial obligations that come with it.

North Carolina’s pretrial release system operates under specific statutory frameworks that define how defendants can secure their release while awaiting trial. The terms “bail” and “bond” have distinct legal meanings, though everyday conversation often blurs the lines between them. Knowing the difference matters because the type of release ordered by a judicial official directly affects what a defendant or their family must do to secure freedom before trial and what financial consequences follow if the defendant fails to appear.

Recent legislative changes have significantly altered North Carolina’s pretrial release framework. Iryna’s Law, enacted as Session Law 2025-93 and effective December 1, 2025, creates new restrictions on pretrial release for defendants charged with violent offenses and establishes rebuttable presumptions against release in certain cases. Understanding how bond and bail work now requires familiarity with these new statutory requirements.

What Is the Difference Between “Bail” and “Bond” in North Carolina?

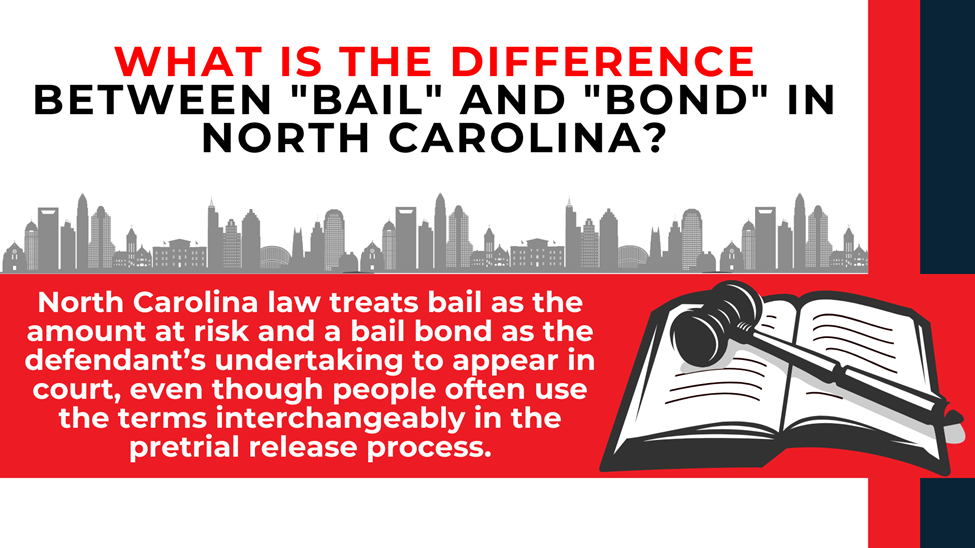

The confusion between these terms is understandable because they are closely related, but North Carolina law treats them as connected but separate concepts in the pretrial release process.

Does North Carolina Law Define These Terms Differently?

North Carolina General Statutes provide specific definitions for bond-related terminology. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-531, a “bail bond” is defined as “an undertaking by the defendant to appear in court as required upon penalty of forfeiting bail to the State in a stated amount.” The statute explains that bail bonds can take several forms, including unsecured appearance bonds, appearance bonds secured by cash deposits, appearance bonds secured by a mortgage, and appearance bonds secured by at least one solvent surety.

“Bail” refers to the amount of money or security that a defendant risks forfeiting if they fail to appear in court as required. When a judge “sets bail,” the judge is determining the dollar amount that will be forfeited to the State if the defendant does not comply with release conditions. The “bond” is the actual mechanism or undertaking that secures the defendant’s promise to appear.

Why Do People Use These Words Interchangeably?

In everyday conversation, people often say “post bail” when they mean “post a bond” or ask “what is the bail amount” when they are really asking about bond conditions. This interchangeable usage occurs because the concepts work together. The bail amount determines the financial risk, and the bond is the instrument that puts that risk into effect. For practical purposes, when someone says they need to “make bail,” they typically mean they need to satisfy whatever bond conditions the court has imposed.

What Does It Mean When a Judge “Sets Bail”?

When a judicial official sets bail, they are establishing the conditions under which a defendant may be released from custody before trial. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-534, the judicial official must impose at least one of several possible conditions. Setting bail involves determining both the dollar amount at stake and the type of bond required. A judge might set bail at $10,000 and require a secured appearance bond, meaning the defendant must actually secure that amount through cash, property, or a surety before release occurs.

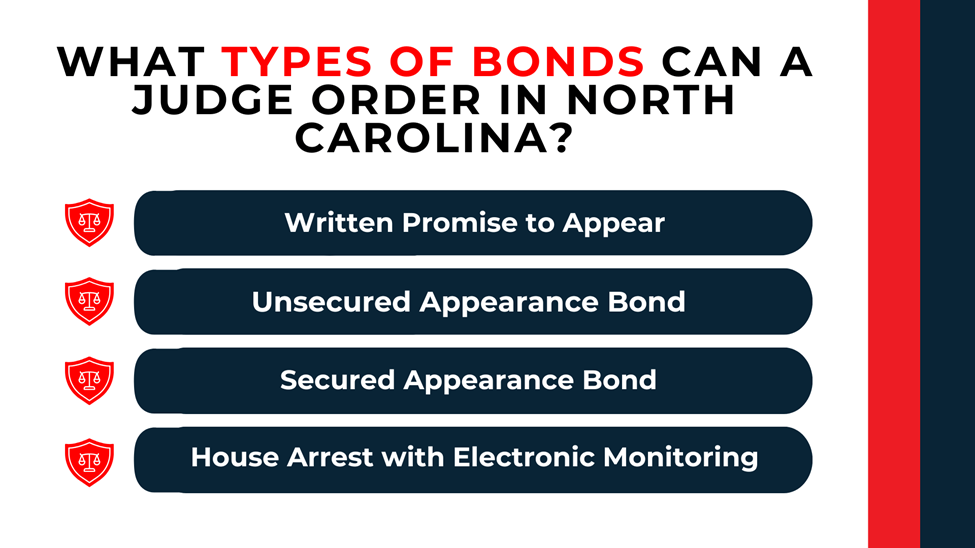

What Types of Bonds Can a Judge Order in North Carolina?

North Carolina law establishes specific categories of pretrial release conditions. Understanding these options helps defendants and their families know what may be required to secure release.

What Is a Written Promise to Appear?

The least restrictive form of pretrial release is release on a written promise to appear. Under this condition, the defendant simply signs a document promising to appear at all required court dates. No money changes hands, and no financial security is required. This option is typically reserved for defendants who present minimal flight risk and pose no danger to the community.

What Is an Unsecured Appearance Bond?

An unsecured appearance bond requires the defendant to sign a bond for a specified amount but does not require payment or security upfront. The defendant promises to pay the stated amount if they fail to appear, but no money or property is pledged in advance. For example, a defendant released on a $5,000 unsecured bond owes nothing unless they miss a court date, at which point they become liable for the full $5,000.

How Does a Secured Appearance Bond Work?

A secured appearance bond requires actual financial backing before the defendant can be released. North Carolina law provides for several ways to secure a bond. The bond can be secured by a cash deposit of the full amount, by a mortgage on real property pursuant to N.C. Gen. Stat. § 58-74-5, or by at least one solvent surety such as a bail bondsman or insurance company.

When families contact a bail bondsman, they are typically seeking help with a secured appearance bond. The bondsman acts as surety, guaranteeing the defendant’s appearance in exchange for a premium.

Under Iryna’s Law, defendants charged with violent offenses face mandatory secured bond requirements. For a first violent offense, the judicial official must impose a secured appearance bond or house arrest with electronic monitoring. For defendants charged with a second or subsequent violent offense—either after a prior conviction for a violent offense or while on pretrial release for a prior violent offense—house arrest with electronic monitoring is required if available. This represents a significant departure from prior law, which gave judicial officials broader discretion in setting release conditions.

What Is House Arrest with Electronic Monitoring?

North Carolina law also allows for house arrest with electronic monitoring as a condition of pretrial release. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-531, this requires the defendant to remain at their residence unless the court authorizes them to leave for employment, counseling, education, or vocational training. The defendant must wear a device that allows a supervising agency to monitor compliance. When house arrest with electronic monitoring is imposed, the defendant must also execute a secured appearance bond.

North Carolina law specifies five conditions that a judicial official may impose for pretrial release:

- Release on the defendant’s written promise to appear without any financial obligation

- Release upon execution of an unsecured appearance bond in an amount specified by the judicial official

- Placement of the defendant in the custody of a designated person or organization agreeing to supervise them

- Requirement of an appearance bond secured by cash deposit, mortgage, or at least one solvent surety

- House arrest with electronic monitoring combined with a secured appearance bond

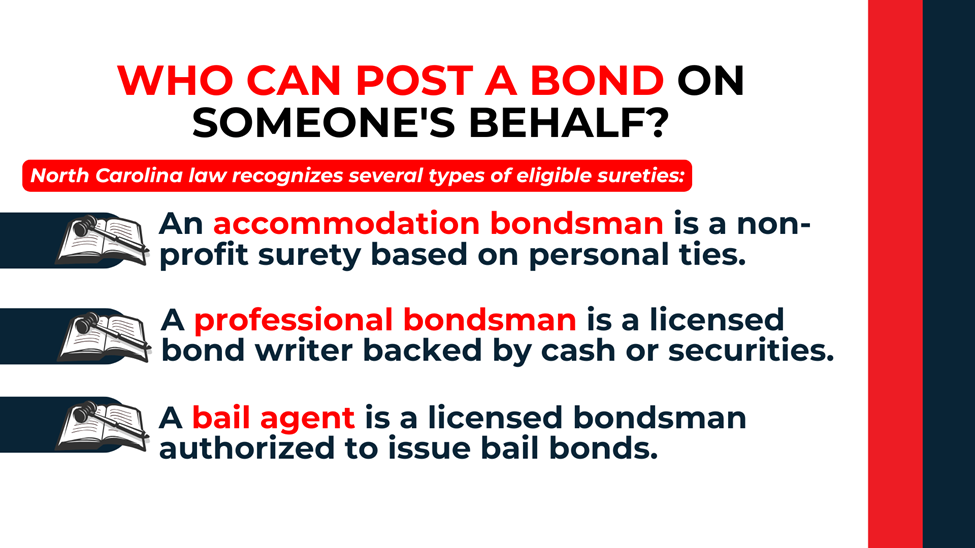

Who Can Post a Bond on Someone’s Behalf?

When a secured bond is required, someone must act as surety to guarantee the defendant’s appearance. North Carolina law recognizes several categories of individuals and entities who can fulfill this role.

What Is an Accommodation Bondsman?

An accommodation bondsman is a natural person who acts as surety out of personal relationship rather than for profit. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-531, an accommodation bondsman is someone who “aside from love and affection and release of the person concerned, receives no consideration for action as surety.” This person must provide satisfactory evidence of ownership, value, and marketability of real or personal property sufficient to cover the bond amount. Family members or close friends who pledge their own property to secure a loved one’s release fall into this category.

What Is a Professional Bondsman?

A professional bondsman is licensed by the Commissioner of Insurance and pledges cash or approved securities with the Commissioner as security for bonds written in connection with judicial proceedings. Unlike accommodation bondsmen, professional bondsmen receive money or other things of value in exchange for writing bail bonds. They operate as a business, using their pledged assets to back multiple bonds simultaneously.

What Does a Bail Agent Do?

A bail agent, also called a surety bondsman, is licensed by the Commissioner of Insurance and appointed by an insurance company to execute or countersign bail bonds on the company’s behalf. The bail agent works as an agent of the insurance company, which ultimately stands behind the bond. When someone contacts a “bail bonds company,” they are typically working with a bail agent who represents an insurance company surety.

North Carolina law recognizes three categories of sureties who can secure a defendant’s appearance:

- The insurance company when a bail bond is executed by a bail agent on behalf of that company

- The professional bondsman when a bond is executed by the professional bondsman or by a runner acting on their behalf

- The accommodation bondsman when the bond is executed by an individual acting out of personal relationship rather than for compensation

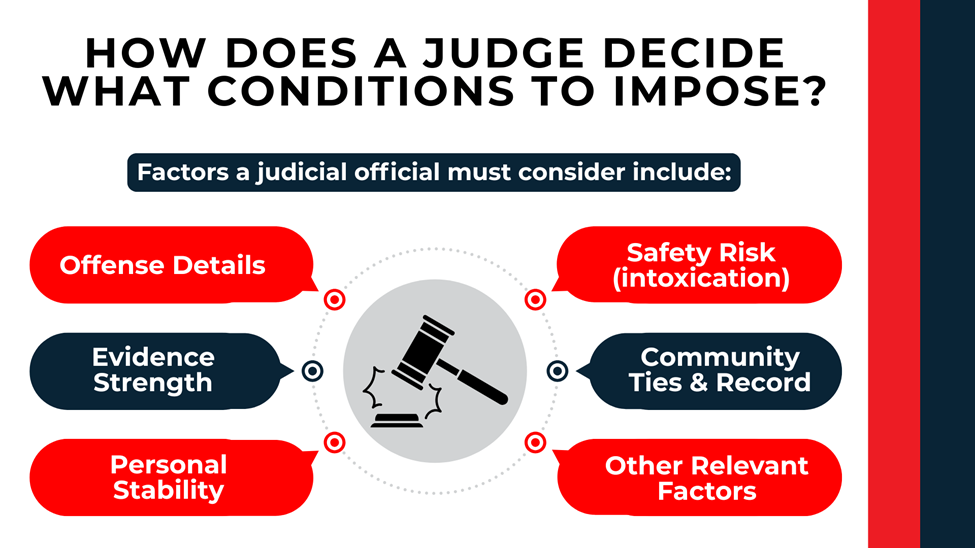

How Does a Judge Decide What Conditions to Impose?

Judicial officials do not have unlimited discretion in setting bond conditions. North Carolina law establishes both the factors they must consider and a presumption favoring less restrictive release conditions—though Iryna’s Law has significantly altered this framework for violent offenses.

What Factors Must the Judge Consider?

Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-534(c), the judicial official must consider available information when determining which conditions of release to impose. The statute requires consideration of multiple factors related to both flight risk and community safety.

The statutory factors a judicial official must consider when setting bond conditions include:

- The nature and circumstances of the offense charged

- The weight of the evidence against the defendant

- The defendant’s family ties, employment, financial resources, character, housing situation, and mental condition

- Whether the defendant is intoxicated to such a degree that release without supervision would be dangerous

- The length of the defendant’s residence in the community

- The defendant’s record of convictions

- The defendant’s history of flight to avoid prosecution or failure to appear at court proceedings

- Any other evidence relevant to the issue of pretrial release

Iryna’s Law added a mandatory requirement that judicial officials direct law enforcement, a pretrial services program, or the district attorney to provide a criminal history report for the defendant and consider that history when setting release conditions. This applies to all defendants, not just those charged with violent offenses.

When Is a Secured Bond Required Instead of Release on Promise?

For defendants not charged with violent offenses, North Carolina law creates a presumption favoring the least restrictive release conditions. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-534(b), the judicial official must impose a written promise to appear, unsecured bond, or supervised custody unless they determine that such release will not reasonably assure the defendant’s appearance, will pose a danger of injury to any person, or is likely to result in destruction of evidence, subornation of perjury, or intimidation of witnesses.

Only after making one of these determinations can the judicial official impose a secured bond or house arrest with electronic monitoring. When imposing these more restrictive conditions, the judicial official must record the reasons for doing so in writing.

However, Iryna’s Law added a mandatory secured bond requirement for any defendant who has been convicted of three or more offenses (each a Class 1 misdemeanor or higher) within the previous ten years, regardless of the current charge.

How Does Iryna’s Law Change Pretrial Release for Violent Offenses?

Session Law 2025-93, known as Iryna’s Law, fundamentally changed pretrial release for defendants charged with violent offenses effective December 1, 2025. The law creates a statutory definition of “violent offense” under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-531(9), which includes Class A through G felonies involving assault, physical force, or the threat of physical force; felony sex offenses requiring registration; offenses listed in G.S. 15A-533(b) such as murder, rape, and kidnapping; and certain specific offenses including discharging a firearm into occupied property and fentanyl trafficking.

For any defendant charged with a violent offense, there is now a rebuttable presumption that no condition of release will reasonably assure the defendant’s appearance and the safety of the community. This shifts the burden significantly. Even if the judicial official determines that pretrial release is appropriate, the law mandates a secured appearance bond or house arrest with electronic monitoring for a first violent offense. For second or subsequent violent offenses, house arrest with electronic monitoring is required if available.

The law also requires written findings of fact explaining the reasons for release conditions whenever a defendant is charged with a violent offense or has been convicted of three or more offenses (each Class 1 misdemeanor or higher) within the previous ten years. Additionally, defendants with three or more such prior convictions must be required to post a secured bond regardless of the current charge.

What Happens If Someone Is Arrested While Already on Pretrial Release?

When a defendant is arrested for a new offense while on pretrial release for another pending case, special rules apply. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-534(d3), the judicial official may require execution of a secured appearance bond in an amount at least double the most recent previous bond, or at least $1,000 if no bond was previously required.

For defendants charged with a felony while on probation for a prior offense, the judicial official must make a written determination about whether the defendant poses a danger to the public before setting release conditions. If the defendant is determined to pose a danger, a secured bond or house arrest with electronic monitoring is required.

Iryna’s Law reinforces these provisions by establishing that defendants charged with a second violent offense while on pretrial release for a prior violent offense face mandatory house arrest with electronic monitoring if released at all. The rebuttable presumption against release applies in these circumstances, making pretrial release significantly more difficult to obtain.

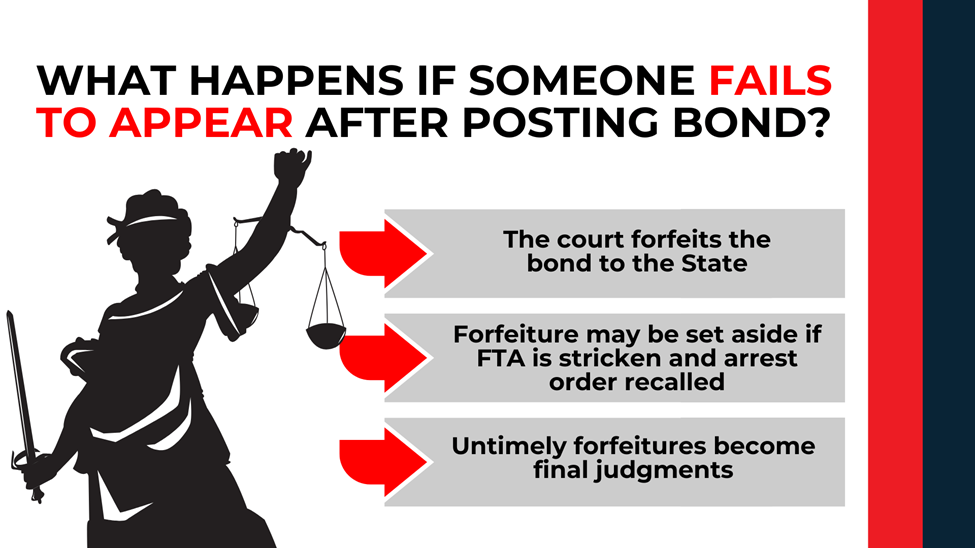

What Happens If Someone Fails to Appear After Posting Bond?

The consequences of failing to appear after posting bond extend beyond potential arrest. North Carolina has detailed statutory procedures for bond forfeiture that can result in significant financial liability.

How Is a Forfeiture Entered Against the Bond?

Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-544.3, when a defendant released on bail fails to appear before the court as required, the court enters a forfeiture for the amount of the bail bond in favor of the State against both the defendant and each surety on the bond. The forfeiture must contain specific information including the defendant’s name and address, the file numbers of the cases, the bond amount, the date of execution, and information about all sureties.

The court provides notice of the forfeiture by mailing a copy to the defendant and each surety at their address of record. This notice must be sent within 30 days after the defendant fails to appear.

Can a Forfeiture Ever Be Set Aside?

North Carolina law provides specific grounds for setting aside a forfeiture before it becomes a final judgment. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-544.5, a forfeiture may be set aside if the defendant’s failure to appear has been stricken and any arrest order recalled, if all charges have been finally disposed, if the defendant has been surrendered by a surety, if the defendant has been served with an order for arrest for the failure to appear, if the defendant died before or within the period between forfeiture and final judgment, or if the defendant was incarcerated in certain facilities at the time of the failure to appear.

A motion to set aside a forfeiture generally must be filed within 150 days after notice is given. The defendant, any surety, a professional bondsman, runner, or bail agent may file such a motion.

What Are the Consequences of a Final Judgment of Forfeiture?

If a forfeiture is not set aside within the statutory period and no motion to set aside is pending, the forfeiture becomes a final judgment under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-544.6. The clerk of superior court then dockets this judgment as a civil judgment against the defendant and each surety. This creates a lien on the real property of the defendant and each surety.

After docketing, the clerk issues execution on the judgment against the defendant and any accommodation bondsman or professional bondsman. Additionally, no surety named in the judgment may become a surety on any bail bond in that county until the judgment is satisfied in full. For professional bondsmen, bail agents, and runners, this prohibition extends statewide.

Why Does Having an Attorney Matter in Bond Hearings?

The bond hearing is often the first opportunity to advocate for a defendant’s release, and the outcome can determine whether someone waits for trial in jail or at home with their family.

Can an Attorney Request Modified Bond Conditions?

Yes. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-534(e) and (f), bond conditions can be modified at various stages of the proceedings. A magistrate or clerk may modify pretrial release orders prior to the first appearance before a district court judge. After that appearance, a district court judge may modify orders. Once a case is before the superior court, a superior court judge may modify release conditions.

An attorney can file motions requesting bond reduction or modification, presenting evidence about the defendant’s ties to the community, employment, family obligations, and other factors that weigh in favor of less restrictive conditions.

How Does Legal Representation Affect the Outcome?

When your freedom is on the line, the quality of your legal counsel is the most critical factor. As one peer noted via Martindale-Hubbell on November 2, 2018: “Patrick is an excellent lawyer and I trust him to handle my important legal matters.”

This trust is built on a deep understanding of how to navigate complex North Carolina laws:

- Tailored Arguments: An attorney understands exactly what judicial officials must consider under state law. Mr. Roberts can present specific evidence—such as proof of employment, family ties, and community involvement—to build a strong case for your release.

- Countering the Prosecution: When prosecutors push for high bonds or restrictive conditions, a defense attorney can step in with specific facts to address those concerns directly.

- Navigating Iryna’s Law: For cases involving violent offenses, North Carolina law often assumes a defendant should not be released. Rebutting this presumption requires showing that release conditions will keep the community safe and ensure the defendant appears in court. Patrick gathers and presents this evidence effectively to counter the legal arguments that would otherwise lead to detention.

Facing Criminal Charges and Need Help with Bond?

Understanding the difference between bond and bail is just the first step. What matters most is having someone who understands how prosecutors approach bond hearings and what arguments actually persuade judges to impose reasonable conditions—especially now that Iryna’s Law has created new presumptions against release for violent offenses.

A Respected and Fearless Advocate

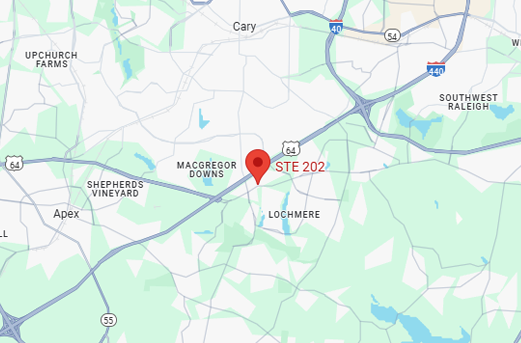

Attorney Patrick Roberts spent years as a prosecutor handling criminal cases before becoming a defense attorney. That experience means he understands how the State evaluates flight risk and danger to the community when arguing for bond conditions. His training at Gerry Spence’s Trial Lawyers College—where he trained directly with and was mentored by Gerry Spence—shapes his powerful approach to persuasive advocacy in every courtroom setting.

As a graduate of the National Criminal Defense College with ongoing training in cross-examination and trial techniques, he brings effective courtroom skills to every stage of a criminal case, starting with the bond hearing.

If you or a family member is facing criminal charges in North Carolina and needs help navigating the bond process, contact Patrick Roberts Law to discuss your situation.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much does a bail bondsman charge in North Carolina?

Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 58-71-95, a bail bondsman cannot accept anything of value from a principal except the premium, which cannot exceed fifteen percent of the face amount of the bond. The bondsman may also accept collateral security or other indemnity, which must be reasonable in relation to the bond amount and must be returned within 15 days after final termination of liability on the bond.

Can bond conditions be changed after they are set?

Yes. North Carolina law allows judicial officials to modify pretrial release orders at various stages of the proceedings. A magistrate or clerk may modify orders before the first appearance, and judges may modify conditions thereafter. For good cause shown, any judge may revoke an order of pretrial release entirely and set new conditions.

What is the difference between a secured and unsecured bond?

An unsecured bond requires the defendant to sign a promise to pay a specified amount if they fail to appear, but no money or property is required upfront. A secured bond requires actual financial backing before release, either through a cash deposit of the full amount, a mortgage on property, or a surety such as a bail bondsman.

Does posting bond mean the charges are dropped?

No. Posting bond only secures release from custody while the case is pending. The defendant remains obligated to appear at all court dates, and the criminal charges proceed through the court system. The bond remains in effect until judgment is entered or the obligation is otherwise terminated under the statute.

What happens to collateral if the defendant appears at all court dates?

Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 58-71-95, collateral security provided to a bondsman must be returned within 15 days after final termination of liability on the bond. The collateral must be returned in the same condition as it was received. Knowing and willful failure to return collateral valued at more than $1,500 is a Class I felony.

What is Iryna’s Law and how does it affect bond decisions? Iryna’s Law (Session Law 2025-93), effective December 1, 2025, created new restrictions on pretrial release for defendants charged with violent offenses. The law establishes a rebuttable presumption against release for violent offenses, requires secured bonds or electronic monitoring for defendants who are released, mandates criminal history review for all defendants, and requires written findings of fact explaining release conditions in certain cases. Defendants with three or more prior convictions for Class 1 misdemeanors or higher offenses within the previous ten years must also post a secured bond regardless of the current charge.

Disclaimer: The information on this website is for general information purposes only. Nothing on this site should be taken as legal advice for any individual case or situation. Case results depend upon a variety of factors unique to each case. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.